Many people with SIBO and even IBS follow Pimentel’s work, and I thought it would be a good idea to read his team’s paper from last February: Defining Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth by Culture and High Throughput Sequencing (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37315761/). The editor of the publishing journal said that the team has “thrown down the gauntlet,” meaning that they are ready to fight to defend their view of SIBO’s definition. I am less interested in the definition of SIBO and more interested in the fact that this paper correlates dysbiosis with digestive problems. I have some real points to make, and of course, I’ll be pulling in chinese Medicine as well. Doing so opens up some new ideas.

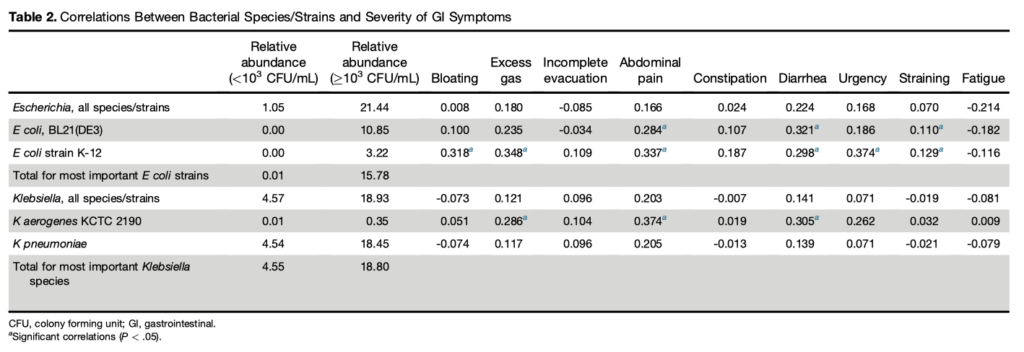

In the February paper, they correlate bacterial overgrowth by species with common SIBO symptoms. The symptoms are bloating, gas, incomplete bowel movements, abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea, urgency, straining, and fatigue. Here’s the summary chart of the most prevalent organisms. If you’re not into charts, stick with me, I’ll explain it:

Connecting dysbiosis with symptoms seems like an important step, but the results are really underwhelming. These bacteria were collected from the first section of the small intestine, the duodenum. I don’t know about you, but I hoped that these strains of E.coli and Klebsiella would correlate closely with the symptoms of SIBO that cause people to suffer. This would really have confirmed the whole concept of SIBO as an illness. The correlations, though, are mostly weak.

I should mention that, in medical research, strong correlations are not always necessary. Even if the correlation between taking a drug and extending life is only .3 or 30%, I think many would choose to take that drug. This “medical standard” is the standard that the Pimentel group is following. However, I believe that people suffering from SIBO or IBS would prefer to see more than a 30% correlation between dysbiosis in the small intestine, and their gastrointestinal dysfunction. Looking at the chart above, most of the correlations are less than 30%. Many are less than 10%. In regular statistics, this actually means that there is no reliable correlation at all (see my note at the bottom).

In my thinking, this indicates two things, both of which could be true:

- These bacterial colonies are better correlated with something else, not a small list of symptoms

- There is more dysfunction in SIBO cases than only dysbiosis in the small intestine

Regarding the first point: There are other correlations that Pimentel’s team could identify, which IMO, break through some of the profound barriers limiting Modern medicine. They could:

- correlate bacterial colonies with a larger list of symptoms

- correlate between symptoms (as a basis of forming syndromes)

- correlation between syndromes

- correlate certain species of bacteria with others species, as aspects of certain syndromes or sets of syndromes.

For a lot of people with SIBO, the word “syndrome” is probably seen as a next to useless word, as in the condition Irritable Bowel Syndrome. But, this has more to do with how syndromes have been handled in medicine, rather than the actual phenomenon of syndromes themselves. At root, syndromes should be constellations of symptoms that have clinical meaning. By “clinical meaning,” I mean that they are treatable.

The Pimentel team could start to take it in this direction. Correlations between colonies of bacteria and those nine symptoms of digestive dysfunction are weak, but if you expand the list of symptoms and start correlating symptoms with other symptoms — basically creating new “types” or syndromes of SIBO — then it is possible to better connect research with the real world. Then, we might see that patients can have more than one syndrome, and that syndromes can even correlate with each other. Lastly, bacteria themselves could be correlated with each other, as aspects of certain diagnosed syndromes.

Look, syndromes are not that different from “patterns” in chinese medicine. Unlike modern medical use of the word “syndrome,” though, which is only used when a biochemical cause has not been found, in chinese Medicine patterns are the cornerstone of diagnosis, and we utilize this framework to the max. Most cases of SIBO will be assessed as having 5-8 patterns simultaneously, each in interrelationship with each other. Also unlike contemporary syndromes, patterns guide treatment.

So, this brings me to the second point: There is more dysfunction in SIBO cases than only dysbiosis in the small intestine. Research has shown that patterns have a physical basis in large intestine dysbiosis, based on stool samples. It isn’t a stretch to speculate that there are also correlations to be found, not just in large, but in small intestine dysbiosis. And, even beyond the small and large intestines, chinese Medicine patterns have been associated with other biochemical anomalies – everything from mitochondrial inefficiency to low stomach acid. These other bodily dysfunctions can be included in the expanded notion of syndrome that I’m proposing. A broad notion like that can capture so much, whereas a specific instance, say of dysbiosis, captures very little.

I am not suggesting that Pimentel’s team incorporate chinese Medicine. Now there’s an idea that would get no traction! However, they could define a new set of syndromes, based on expanded research — one that is thoroughly Western in it’s orientation. The problem is that it would be holistic, and that is just against the grain of their project and medical science, in general. I don’t think his team will do it, but it would benefit everyone, IMO. Just think… you would be able to identify, at least in a correlated sense, your dysbiosis, as well as other internal factors, just by the specific symptoms you are manifesting.

Symptoms mean more than what most people think. Certainly they mean more than what regular doctor’s think. The problem is that our cultural approach to medicine prevents us from making sense of them. It also reduces our ability to even discern and differentiate them. Take “thirst” as an example. Feeling thirsty or lacking thirst is a symptom about which most GI doctors will not ask questions. I don’t see it mentioned much on digestive disorder forums either, and when it is brought up, it is not differentiated. It should be. Some people with digestive disorders have no thirst. Some have thirst but no desire to actually drink anything. Some have only a dry mouth, but no thirst. Others have copious thirst. Some can only enjoy warm drinks, others cold drinks, and others only feel thirsty at night. There are distinct possibilities, and they all mean something about the condition of the body.

Searching for causes may ultimately be of limited benefit because they are too simplistic. The treatments they produce do not cure the condition, except in a relatively small percentage of patients whose condition precisely matches the research. I believe we see the limitations of the search for medical causes on a daily basis.

The bigger point that I’m trying to make, though, is that we must find better routes to individualized treatment. People with chronic disorders are experimenting on themselves to find that special combination of substances and behaviors that will heal their particular case. Individualized treatment approaches are the key to sorting out treatment possibilities in advance of trying them. Expanding the notion of syndromes is a way to move in that direction. Patterns, as they are defined in chinese Medicine, already exist and are just waiting to be explored by Western researchers and redditors alike. Unlike our contemporary use of “syndromes,” all patterns in TCM are treatable. For those in the modern west, it is, quite literally, an unexplored continent of medicine.

Note: academics may gripe about my turning correlations into percentages, but it makes them easier to discuss in conversation. Percentages can be added together. Correlations cannot.

(originally published on reddit, August 2024)

u/somasavant