In an age of distrust, personal experience becomes king. No one can try everything, so we have to rely on reports from others, often turning to Reddit and other platforms to discuss as much as we can. A loose screening of people takes place in these forums to decide whose words can be trusted and whose cannot. Of course, people have their agendas, and everyone knows it. But the bigger, often-undiscussed issue is that a person’s experience can be tainted — or missing altogether — for very personal reasons. Consider this story:

A man, who was afraid of heights, traveled to the southern rim of the Grand Canyon. After driving for ten hours, he parked his car 500 feet away and then walked 250 feet towards the perilous edge. He stopped at that great distance and stood there for a while, far from the actual view. Eventually, he turned around, walked back to his car, and drove home. His friend later asked, “So, how was the Grand Canyon?” and the man replied, “Well, I wasn’t really impressed…”

The question is: Who should be believed and why? It is very common for someone to trust because of feelings and not facts. A nurse once commented to my friend, “Oh, you do acupuncture. I’ve always wanted to try that!… except that it’s the work of the devil.” My friend — who is a very conscientious and trustworthy person — was floored by what this nurse said. You can see from the comment, though, that even when there is a desire to try something different (like another medical system), it can fall on the side of things one just doesn’t do. It can look like an unwise action — or even a moral dilemma — for some people. Everyone has their boundaries, but I wonder whether it’s because sticking with what’s familiar, even if it lets you down again and again, is… well, familiar. Familiar things have the quality of family. Can we say such a thing? That the standard medical system — or the online forums that espouse its concepts — are psychologically like family to some people? Yes, we can. I see it again and again when people staunchly live out the idioms and perspectives of standard medicine. They don’t notice that the divisions they make about what is true and what is false (or the work of the devil) are not so black-and-white. Life is complex and multifaceted, and our approaches to health, while still being careful and rigorous, should also reflect this fact.

The situation of trust reminds me of my great-grandmother, who would only ever use Ivory-brand soap. Ivory’s claim to “purity” with that white packaging — and the fact that it floats! — represented something to her. Never mind that this was marketing, with an ounce of truth, because for my grandmother, it was something clean in a fairly dirty world.

Much later, when my mother saw me using Ivory soap as an adult, she said, “Grammy would be proud.” I felt family values transmitted in that simple sentence. This is fine, but not if they cannot be separated from being sold a story. With no offense meant towards my mother, purity is open to interpretation. Ivory soap, for example, has synthetic chemicals and isn’t organic. These facts might matter — or they might not — but they are facts. In a bygone era, that soap may have been the best choice on the shelf. Sometimes, though, we have to ask ourselves: what exactly are we continuing, and why? If a person’s commitment to standard medicine is like this, I can see why they might believe it is wrong to stray from the standard perspective regarding their health. It’s like shopping for the wrong soap — heaven forbid.

In Western civilization, skepticism is an important moral container, because it is seen as a way of staying on the side of truth. At one time, this was a revolutionary idea. In the late 1500s, thinkers such as Francis Bacon and René Descartes began questioning what we can know for certain and what we might be misled about. Similar to the comment from the nurse about acupuncture, these great thinkers framed skepticism as a way of escaping the grips of the devil and moving human beings closer to God. In other words, like my grandmother, they were searching for purity. In their case, through truth-seeking, their thoughts actually laid the foundation for modern science.

Skepticism, though, should not be a way of identifying truth from falsehood. It should be a way of separating fact from fiction, and there is a difference between these two ways of thinking. Truth often implies allegiance; facts require observation. While searching for truth narrows our frame of view, examining facts actually widens it. This difference in stance changes everything. An attachment to truth serves to perpetuate conformity to established systems and norms. Even for those who embrace skepticism by trying to doubt everything, they naturally and unconsciously embrace the familiar and rule out the unfamiliar. This causes truth seekers (instead of fact finders) to continue using the same soap, whether it is truly pure or not.

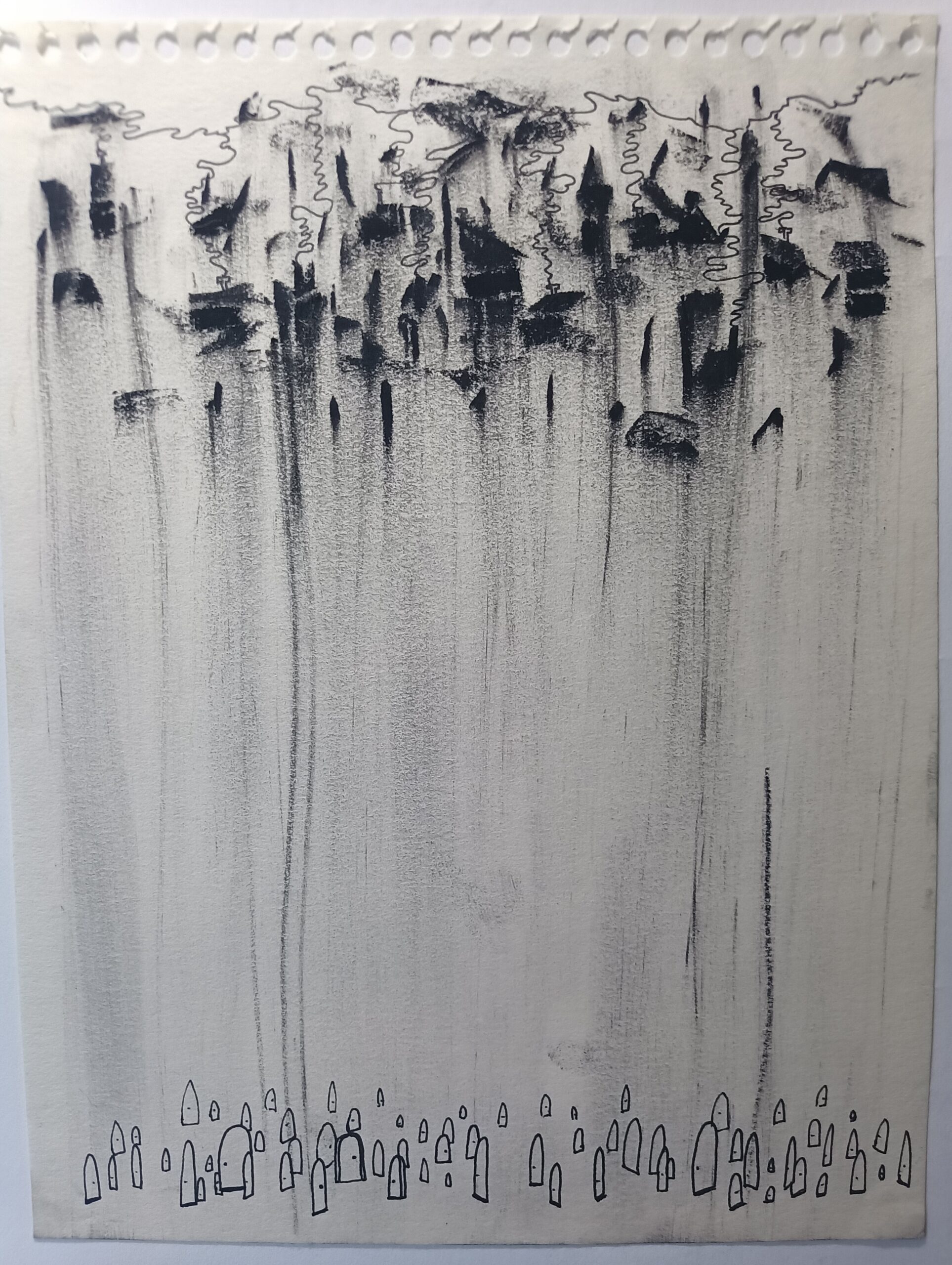

The fear of the unknown, the impure, the foreign, and the potentially harmful runs deeply — and more so when we’re ill. Our reserves are already tapped, our spirit worn thin, and we may no longer see ourselves as we once did. Could taking an uncommon path push us into becoming someone else? What exactly are we risking?

The breaking point for an individual can come when what they expected from doctors and the medico-scientific community ends up being very different from their actual, personal experience. Incredibly, when this happens, it is a moment of both liberation and entrapment. You become liberated because you can see what had been unseen. You’re further trapped because now you have to navigate the situation — and the maze broadens and deepens.

Exaggerated expectations of modern medicine are cultivated by society and shouldn’t be. That allegiance — and the fanfare surrounding it — becomes morally problematic when it dismisses personal experience that does not fit the mold, or defers present medical need to some future moment when science is expected to “figure it out.” Many people with digestive disorders — like IBS or SIBO, and related conditions — experience disappointment because the scientific system and doctors they trusted could not follow through when it finally counted. Lab results touted by researchers can correlate poorly with actual symptoms. Yet the frameworks guiding patients’ choices are treated as unshakable — even when the lived experience says otherwise.

I once saved the shoulder of a Buddhist priest. His surgeon had recommended a complete replacement of the joint. The surgery was a month away, and because of his anxiety, the priest came for acupuncture with very little hope. We actually made quick progress, and the surgery was cancelled. While on the treatment table, as I was working with moxa, it finally dawned on the priest that he would not have to get surgery. He began repeating aloud, “so ignorant, so ignorant, they’re so ignorant…” — referring to his doctors and surgeons. Isn’t it funny that because he was a Buddhist priest this memory stands out to me?

When we forgo actual experiences — of risk and healing — either because we overly yield to authority or the words of others, we may leave ourselves blind. No amount of explaining can overcome the gap between seen and unseen. Our vision can become dim, as if through a glass darkly.

If you don’t know about the Grand Canyon, it is an absolutely astonishing work of natural wonder. I’ve been there. Similarly, I encourage people to notice and describe their actual experience of illness. Symptoms are incredibly important to unravelling a digestive disorder, but too often they are discredited — by family, friends, and even doctors — and replaced by a name: IBS, colitis, GERD, SIBO, or whatever.

More than people realize, this can interfere with actual healing, because it takes something very individual and makes it general. Diseases and disorders cannot be healed. Only people can be healed. When we overly lean on the purity of medicine, we might also inoculate ourselves from this experience.

I can assure you of one more thing: skepticism is sometimes used to redirect mistrust toward those who deserve it least — but that’s another story.

This post was revised in February 2026 to clarify several sections.

Leave a Reply